i saw a dragon

at the beach, a bird upon

a limb of driftwood

The Tuileries

“You look like a woman on a mission,” said the guard as I passed into the Tuileries exhibit – I was back for a second look at Camille Pissarro’s bird’s eye view paintings – delicate and atmospheric tracings of the changing seasons in the Garden. Sit on the bench nearby, where you can also observe the sparkling, light-filled works of Childe Hassam and Gaston de LaTouche. In the next room are lovely Gelatin Silver prints from the 1960’s ¬ 1980’s by Kertesz, Cartier-Bresson, Kenna, and Poncar that take you to serene, yet lonely places.

Marble and bronze statues are an integral part of the Garden and of this exhibit – my favorites are Hippomenes (1712) and Atalanta (1704) in the midst of their footrace (we have the chance to see the originals, here). Other pairs of statues illustrate popular mythology (the Fawn & Hamadryad, Vertumnus & Pomona) – but you must see them to feel their majesty. There is a lot more to see in this exhibit at the Portland Art Museum, including etchings of a hot air balloon ascent (Ben Franklin was there), and political satire. Perhaps I’ll see you there!

speaking of influences

I came to printmaking through the back door of photography. I include Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston and Ansel Adams as strong influences on my work. All three were members of Group f/64 whose photographs were characterized by maximum image sharpness of both foreground and distance. The group’s work celebrated the beauty inherent in landscapes, plants, found objects and the figure. F/64 also promoted the use of straight photographic techniques without special manipulation in the darkroom. I embrace many of these principles as an intaglio printmaker using traditional methods and tools.

As a student printmaker I was introduced to the work of Martin Lewis. Lewis’s prints are a celebration of light and texture. Using the most primary of printmaking methods (lots of drypoint), Lewis was able to express the delicacy of backlit textiles, detail within shadows and reflective surfaces. His ability to suggest facial features and emotion with a similar light touch both inspires and challenges me.

Studying the early prints of Jim Dine motivates me to be less reverent and restrained in my mark making. His work has an expressive, energetic looseness that remains an elusive goal for me. As I move forward in creating prints I aspire to combine the delicacy of Lewis, the energy of Dine and the technical honesty of Cunningham, Weston and Adams.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Gene Flores. It was his suggestion to try printmaking that started my education as an intaglio printmaker. It is his example of productivity and consistently high quality of work that challenges me to move forward and try harder.

Influences

I grew up in a smallish town, where things like art weren’t readily available. It wasn’t an unusual suburban experience; I played baseball and basketball like a lot of kids, I went to see movies when I could. I still remember an audience I was part of giving a standing ovation to the end of “The Karate Kid.” Just a random screening some weekend, and all of us loved the ending so much we all stood up and applauded at the screen, with no one involved with the making of the movie within a thousand miles of the theater.

But things like movies seemed like they were undoable. There wasn’t really the idea of authorship of a film; the credits, even for a basic, uncomplicated movie, still comprised an army of experts all working towards the same goal. TV shows were the same way, records… No matter how much I loved a given record, there was still scores of names involved in the making. Everything from musicians to producers to songwriters to lawyers and agents… Books were the one thing that someone could make, but not just anyone could make a book. It probably took me until middle school before I read a novel by an author that was actually alive, and there weren’t many Maya Angelou’s wandering around in my life, that I could ask about how she sat down and wrote “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.”

Eventually, my friends started collecting baseball cards, and then comic books, and then I started actually reading comic books. I became aware that they were made by actual people, people who had differing levels of skill, and I figured that I could perhaps master one of those skills and be one of those guys involved in making comic books. That seemed like an attainable goal. Most comic books were made by four or five people; a writer, one or two people doing the artwork, someone who made all of the word balloons readable and neat, and someone who colored in the artwork. On top of that, there was an editor who oversaw the whole process. That’s just how things were done – assembly line production.

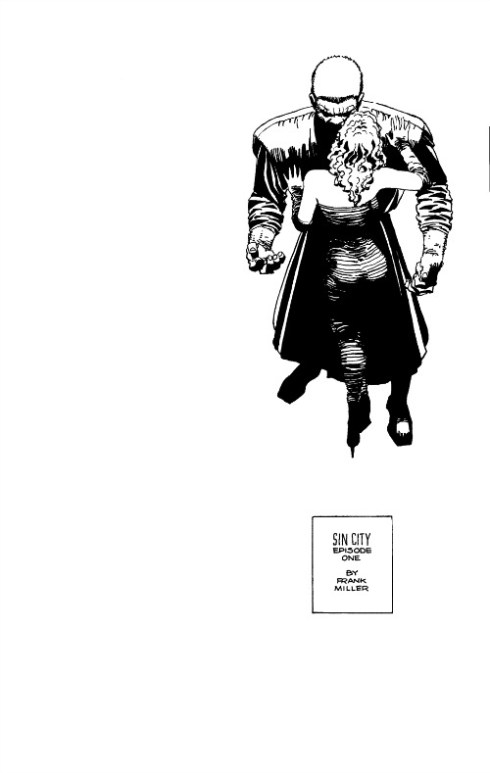

When I was 15 years old, Dark Horse Comics (from nearby Milwaukie, OR) published the first installment of a story called “Sin City.” This is what the first page looks like:

It’s a beautiful drawing, in a style rarely used in comics at the time. But that’s not what caught my eye. This was:

By Frank Miller.

Well, who wrote it? Who lettered it?

By Frank Miller.

You mean he did everything? That’s not possible, where are the rest of the credits? There are no more credits. This was the first time that I’d seen an entire comic book from one hand before. The pinnacle of cartooning was no longer mastering one skill, it was mastering ALL the skills. This small box expanded the parameters of what I figured was possible. At that point, “By Clayton Hollifield” became my new mission.

Film director Robert Rodriguez (“Spy Kids,” “Desperado”) put it a little more elegantly in his book, “Rebel Without a Crew,” which I’d stumble across in college. He’s talking about film, but this is some serious life advice:

“…there are extreme benefits to being able to walk into this business and be completely self-sufficient. It scares people. Be scary.”

Frank Miller’s “Sin City” is how a kid got introduced to the idea of art, where there was no art anywhere, as far as the eye could see. The idea that you could create anything you wanted, without compromise, so long as you had the skills to make it a reality was a pretty damned attractive one.

-clay

Exhibit at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Salem OR

I recently saw the current retrospective of Richard Elliot’s work. There was an article about it in the Oregonian a few weeks ago, and it described in particular the work that he made with reflectors. When the article also stated that flashlights would be available to view the show, I knew that I had to go. I was not disappointed, and, in fact, the experience far exceeded my expectations. His aesthetic was consistent: bright colors, elaborate geometric patterns, and lots of visual glitter (sometimes literally!). The work evokes all types of genres: stained glass, indigenous art, op art, folk art, ……. And when the light from a hand-held flashlight bounced off of those reflectors, the result was pure magic. I saw the show with my friend Deb Spanton, and we both walked out with smiles on our faces. The exhibit includes a wonderful, short filmed interview with him and his artist wife Jane Orleman, and the happiness in his life comes through in his work. The show will be up until July 20, 2014. Go and see it!